Rain is a part of life in the Pacific Northwest, and it’s mostly a good thing. But too much rain can cause flooding, especially when the water hits hard surfaces such as pavement and roofs and doesn’t soak into the ground. Rain can also become a carrier of pollution, since water picks up everything in its path and delivers it to the nearest waterway. There’s plenty that Shore Stewards can do to reduce pollution in local creeks, rivers, lakes and streams.

In this Guideline:

-

References for Guideline 4

-

Protecting Washington’s Waters from Stormwater Pollution, PUB # 07-10-057, 8 p, Washington Dept. of Ecology, July 2007.

Working for Washington’s Future: Healthy Watersheds, Healthy People, PUB #08-01-018, Washington Dept. of Ecology, May 2008.

Washington State Deptartment of Ecology Water Quality Webpage, http://www.ecy.wa.gov/programs/wq/wqhome.html, includes information and links on

Ground and Surface Waters, Nonpoint Pollution, Puget Sound Water Quality, Stormwater Permits, Wastewater Treatment, and more.

LID Technical Guidance Manual for Puget Sound, Curtis Hinman and Bruce Wulkan, 346 p, WSU Extension and Puget Sound Partnership, 2012.

Rain Garden Handbook for Western Washington, Curtis Hinman, 96 p, WSU Extension, June 2013.

-

Using Low Impact Development (LID) Methods

-

Good stormwater management not only prevents damage to property and people from flooding, but it also protects the quality of our water. Stormwater management is done by most cities and towns at a large scale, but you can do a lot on your own property to help out. These home-based Low Impact Development (LID) techniques include rain gardens, permeable pavement, rainwater catchment, and soil amendments for better absorption.

Good stormwater management not only prevents damage to property and people from flooding, but it also protects the quality of our water. Stormwater management is done by most cities and towns at a large scale, but you can do a lot on your own property to help out. These home-based Low Impact Development (LID) techniques include rain gardens, permeable pavement, rainwater catchment, and soil amendments for better absorption.LID can be applied to new development or an existing home and can be successful in many different situations from urban to rural. Some techniques are simple and others require some engineering. All require a good understanding of how water flows to and from your home and land.

LID DOESN’T BELONG EVERYWHERE: There are certain situations when Low Impact Development practices are not advised or recommended. While infiltration of rainwater into the soils is usually desirable, directing water to some locations can create problems with septic system drainfields, may flood crawlspaces, or de-stabilize slopes and bluffs. Check out the Washington Department of Ecology’s “Managing Drainage on Coastal Bluffs” publication and seek professional advice regarding drainage methods if needed. Refer to Guideline 5 for more information about reducing erosion and landslides.

Some LID techniques you might consider for your own property include:

- Preservation. Keep as much of the desirable, existing soils and ve

getation as possible.

getation as possible. - Amending soils. Adding compost to soils disturbed during construction allows you to restore the soil’s health and ability to infiltrate rainwater. This is also something that can be done with your existing property.

- Pervious paving. Alternative forms of asphalt and concrete paving allow rainwater to soak through the paving rather than flowing across it. Pervious pavers and grids are also available. These options provide filtration, reduce runoff, and enable water to soak in to replenish groundwater.

- Rain gardens. A rain garden is essentially a shallow depression constructed to fit your yard, that uses a special soil mix and a variety of plants specifically selected for rain gardens. The soil mix supports plant growth, holds moisture and allows the water to soak in. Rain gardens are not suitable in every location, especially near a bluff. More information can be found at raingarden.wsu.edu.

- Rooftop rainwater catchment system. Installation of a rain barrel next to your home allows you to collect rainwater, conserving it for future use in your yard and garden. Several can be installed, or you might want to collect more rain through use of a cistern. For every 1,000 square feet of rooftop, you can collect over 600 gallons of water for every inch of rain that falls on the roof! Websites contain information on creating a variety of rain barrel systems and cistern systems.

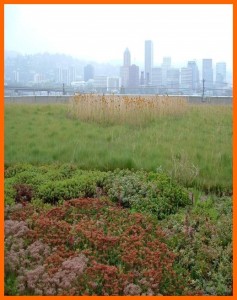

- Vegetated (green) roofs. Top your structure with plants instead of shingles, helping you to reduce pollutants and slow down roof water runoff. Make sure your building can bear the weight of snow and soil before doing so.

More information about low impact development strategies can be found at raingarden.wsu.edu/

Green roof

- Preservation. Keep as much of the desirable, existing soils and ve

-

Preventing Pollution

-

Simple actions can help reduce pollution in our local waters. The main idea is to stop pollutants from reaching impervious surfaces on the ground, where the next rainstorm could carry them into a storm drain and into a nearby creek, lake, or Puget Sound.

Simple actions can help reduce pollution in our local waters. The main idea is to stop pollutants from reaching impervious surfaces on the ground, where the next rainstorm could carry them into a storm drain and into a nearby creek, lake, or Puget Sound.You can help by:

- Maintaining your car and driving it less. Maintain your vehicle by making sure all fluid leaks are fixed. If you do your own maintenance, recycle used motor oil, antifreeze, and other fluids. Vehicle exhaust contains many contaminants that end up on the road and ultimately in stormwater. Driving less and driving a low emission vehicle will reduce the amount of harmful pollution.

- Washing vehicles. Wash your car or boat at a commercial carwash where water is collected and treated. If you wash vehicles at home, do it over a part of the lawn that allows water to soak into the soil, not on the pavement—and use a mild, phosphate-free soap. Never wash your vehicle over your septic system or drainfield, which could harm your septic system.

- Disposing of fluids properly. Never dump fluids including solvents, paint, herbicides, pesticides, fertilizers, or other harmful fluids or chemicals into a storm drain or ditch. These eventually drain to a stream, wetland, beach, or groundwater.

- Reducing fertilizer and pesticide usage. Minimize or eliminate your use of fertilizers and pesticides. Avoid fertilizing before a rainstorm. See Guideline 3 for more information.

- Maintaining your septic system. If you have a septic system, have regular inspections and pumping to avoid system failure. A failing septic system allows sewage to seep to the surface of your yard where children and pets can get into it and rain runoff could carry it to local waterways.

- Disposing of pet waste. Pick up pet waste, bag it, and dispose of it in the garbage. Keep animals and livestock out of streams, Pick up and store manure in a covered area, making sure it does not wash into nearby waterways.

- Reducing rooftop runoff. Direct your downspouts to a place where water can soak in to the ground, and not to a driveway or the storm drain in your street.

- Educating yourself and your family. Learn about your local watershed. Consider volunteering for stream restoration or other local volunteer projects. You will learn a lot about where your water comes from, where it goes, and how healthy it is.

Good stormwater management not only prevents damage to property and people from flooding, but it also protects the quality of our water. Stormwater management is done by most cities and towns at a large scale, but you can do a lot on your own property to help out. These home-based Low Impact Development (LID) techniques include rain gardens, permeable pavement, rainwater catchment, and soil amendments for better absorption.

LID can be applied to new development or an existing home and can be successful in many different situations from urban to rural. Some techniques are simple and others require some engineering. All require a good understanding of how water flows to and from your home and land.

LID DOESN’T BELONG EVERYWHERE: There are certain situations when Low Impact Development practices are not advised or recommended. While infiltration of rainwater into the soils is usually desirable, directing water to some locations can create problems with septic system drainfields, may flood crawlspaces, or de-stabilize slopes and bluffs. Check out the Washington Department of Ecology’s “Managing Drainage on Coastal Bluffs” publication and seek professional advice regarding drainage methods if needed. Refer to Guideline 5 for more information about reducing erosion and landslides.

-

Understanding the Impacts of Runoff

-

After a rainstorm, you have probably noticed water running over large flat surfaces, such as parking lots, roofs, driveways, sidewalks, farm fields, roads, and lawns. This surface water runoff is known as stormwater. As we replace forests and fields with hard impervious surfaces, more rain runs off the land instead of soaking into the soil. This increases the amount of stormwater runoff, which has been identified as the leading contributor to water quality pollution in the Puget Sound. Pollutants carried by stormwater, such as heavy metals, petroleum products, excess nutrients and pathogens, have harmed many creeks, lakes, rivers and bays in Washington.

After a rainstorm, you have probably noticed water running over large flat surfaces, such as parking lots, roofs, driveways, sidewalks, farm fields, roads, and lawns. This surface water runoff is known as stormwater. As we replace forests and fields with hard impervious surfaces, more rain runs off the land instead of soaking into the soil. This increases the amount of stormwater runoff, which has been identified as the leading contributor to water quality pollution in the Puget Sound. Pollutants carried by stormwater, such as heavy metals, petroleum products, excess nutrients and pathogens, have harmed many creeks, lakes, rivers and bays in Washington.Orca whales, two species of salmon, and bull trout are protected under the federal Endangered Species Act and are threatened with extinction. Loss of habitat due to development and stormwater pollution are both contributing factors to their status. Shellfish harvesting at many of our beaches is restricted or prohibited due to pollutants carried in stormwater runoff.

Some other effects from stormwater runoff include:

- Property damage. Flooding has increased in some areas because water can‘t soak slowly into the ground. Instead it runs off hard surfaces and, in a heavy rain, can lead to flooding, erosion and property damage.

- Water pollution. Water becomes polluted as it runs across lawns, driveways and other hard surfaces, when it collects oil, gas, fertilizers, pet waste and more. Water eventually carries these contaminants to our lakes, streams, rivers, wetlands, and marine waters.

- Beach and shellfish closures. Bacteria, viruses and other pathogens from pet and livestock waste, as well as failing septic systems can close beaches for swimming and shellfish harvesting, as well as harm pets and wildlife.

- Increased algal growth. Nutrient pollution from livestock manure, croplands, landscape runoff, and failing septic systems can cause excessive algal growth. As the algae die and decompose they consume dissolved oxygen in the water to the detriment of fish and other organisms that need it.

- Clouded water. Sediment (loose soil) can cause turbidity (cloudiness) in water, reducing the amount of light penetrating the water. This inhibits growth of aquatic plants that fish and shellfish depend on. It can also clog up the gravel in streambeds that salmon use to lay their eggs in. Sediment can enter stormwater from construction sites, eroding stream banks, agricultural fields, and other disturbed areas.