Most shoreline and bluff landowners are keenly aware of the problems that can occur from erosion and landslides. We’ve all seen media coverage of a home teetering on the edge of a bluff, lives lost in a mudslide, and floods sweeping entire neighborhoods away. This guideline will give you a better understanding of how water moves and how erosion occurs, as well as what steps you can take to reduce risks.

Words to Know:

Bulkheads: manmade structures constructed along shorelines to control beach erosion.

Seawalls: hard engineered structure of considerable length, built parallel to the shore to prevent erosion from wave action.

Riprap: a sustaining wall of stones or chunks of concrete piled together to prevent erosion from wave action.

Littoral Drift: the process by which beach sediment is moved along the shoreline.

Forage Fish: small fish which are preyed on by larger predators for food. (surf smelt, Pacific herring, Pacific sand lance)

Soft shore protection: natural shoreline protection, including vegetation and drift logs, as an alternative to bulkheads, seawalls and riprap.

Tightline: tightline (a closed pipe) that carries water to a safe point below the slope.

In this Guideline:

-

References for Guideline 5

-

Surface Water and Groundwater on Coastal Bluffs: A Guide for Puget Sound Property Owners, Myers Biodynamics with Lorilla Engineering, 64 p, Washington State Dept. of Ecology PUB 95-107, June 1995.

Slope Stabilization and Erosion Control Using Vegetation, Rian Myers, 42 p, Washington State Dept. of Ecology PUB 93-30, May 1993.

Vegetative Management: A Guide for Puget Sound Bluff Property Owners, Elliott Menashe, 46 p, Washington State Dept. of Ecology PUB 93-31, May 1993.

The Tide Doesn’t Go Out Anymore: The Effect of Bulkheads on Urban Bay Shorelines, Scott L. Douglass and Bradley H. Pickel, University of South Alabama, 2006.

Mitigating Shore Erosion along Sheltered Coasts, National Research Council of the National Academies, 188 p, 2007.

Soft Shore Protection as an Alternative to Bulkheads, Jim Johannessen, 13 p, Padilla Bay National Estuarine Research Reserve.

-

Living on Bluffs – Diverting runoff to the beach from your bluff

-

If you live at the top of a bluff, taking care of your water runoff is critical. Homeowners have caused landslides by directing water over bluffs. The routing of surface runoff to the beach in a tightline (a closed pipe) is standard practice in the Puget Sound region, although the degree to which it helps is highly site dependent. It is important to make sure that pollutants do not enter the tightline as they will be flushed directly into the water.

If you live at the top of a bluff, taking care of your water runoff is critical. Homeowners have caused landslides by directing water over bluffs. The routing of surface runoff to the beach in a tightline (a closed pipe) is standard practice in the Puget Sound region, although the degree to which it helps is highly site dependent. It is important to make sure that pollutants do not enter the tightline as they will be flushed directly into the water.- Designing and constructing a tightline. If your groundwater and/or surface waters are tightlined to your beach, it is very important that these lines are properly designed, constructed, and maintained. The tightline pipe material has to be sufficiently strong to withstand the elements, anchored securely to the bluff, and not perforated. Water from a tightline should never be discharged at the top or middle of a slope.

- Choosing a discharge point location. Carefully consider the discharge point location for your tightline. An energy dispersion device or method should be used at the discharge point to prevent beach erosion.

- Checking tightlines regularly. Vegetation should not be allowed to cover the tightline, so you easily inspect the line to ensure that it remains securely fastened and that there are no leaks. If you find a maintenance problem, be sure to fix it immediately to ensure bank stability. Inspect your tightline and its discharge after a major storm. Tightlines can fail during large storm events, concentrating huge flows of water onto your bluff face. They can also be damaged by falling tree limbs, small landslides, and by heavy winds. They can be clogged by ice, debris, and animal nests, so you need to check regularly during the rainy season to verify that water runoff is actually exiting the lower end of the pipe. If there is a failure, severe erosion can occur over a very short period of time.

- Checking the regulations. Consult your county or city regarding current regulations and resources that can help with site assessment, design, and construction. Some tightline materials and installment methods may not be allowed in your area, so it is important to check before installing.

-

Living on Bluffs – Living at the base of a bluff

-

Many beachfront communities in the Puget Sound region were built along the shoreline on a flat area at the base of a bluff. These communities are often accessed by roads that cut across the bluff, often zig-zagging down the bluff’s face. Up until the practice was halted by the state in the 1960s, some developers would use heavy equipment and large hoses to wash bluff material down the slope and onto the beach, creating a base of soil, dirt and rocks on which they could build new homes. In many of these locations, these were originally feeder bluffs, naturally eroding to nourish the beach below. If your home is in one of these communities, between the bluff and shoreline, you should consider what actions you and your neighbors can take to minimize the likelihood of slides.

Many beachfront communities in the Puget Sound region were built along the shoreline on a flat area at the base of a bluff. These communities are often accessed by roads that cut across the bluff, often zig-zagging down the bluff’s face. Up until the practice was halted by the state in the 1960s, some developers would use heavy equipment and large hoses to wash bluff material down the slope and onto the beach, creating a base of soil, dirt and rocks on which they could build new homes. In many of these locations, these were originally feeder bluffs, naturally eroding to nourish the beach below. If your home is in one of these communities, between the bluff and shoreline, you should consider what actions you and your neighbors can take to minimize the likelihood of slides.If there are trees on the slope behind you, leave them in place whenever possible. If they appear to be in danger of falling onto your house, contact a reputable arborist to determine the health of the trees prior to removing them. You should also leave native vegetation in place. These trees and plants help stabilize the bluff with their root systems and by removing water from the soil and transpiring it into the air. If neighbors at the top of the bluff want to cut trees on or near the bluff’s edge you may want to discuss your slope stability concerns with them. You should also check with your planning department, since removing or topping the trees may not be allowed within a certain distance from the bluff’s edge. Guideline 2 offers alternatives to topping or cutting trees by pruning in a manner that retains or improves the view, yet not harming the health of the tree.

If there are roads or pathways down the slope, have an engineer design a method to channel runoff along these hardened surfaces to the beach without flowing down or across the slope and causing erosion. Do not try to dig ditches or channel the water yourself, as this can do more damage than good.

-

Living on Bluffs – Understanding bluff anatomy

-

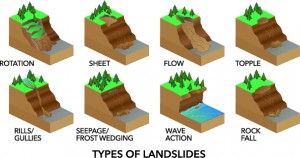

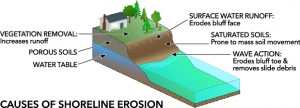

On the upland side (top of bluff), slope failures may occur as a result of water buildup in the soil. This can happen naturally, or as a result of development activities, clearing of vegetation, and modification of site drainage. At the bottom of a bluff, waves and fluctuating high water levels due to tides can undercut the toe of the bluff and cause collapse. In both cases, bluff erosion is usually due to a combination of water and gravity, with the encroaching influence of development adding to the natural erosion. Our rainy climate keeps our soil moisture levels high the majority of the year, and can be at or near the saturation point during the wet months of winter.

On the upland side (top of bluff), slope failures may occur as a result of water buildup in the soil. This can happen naturally, or as a result of development activities, clearing of vegetation, and modification of site drainage. At the bottom of a bluff, waves and fluctuating high water levels due to tides can undercut the toe of the bluff and cause collapse. In both cases, bluff erosion is usually due to a combination of water and gravity, with the encroaching influence of development adding to the natural erosion. Our rainy climate keeps our soil moisture levels high the majority of the year, and can be at or near the saturation point during the wet months of winter.

-

Living on Bluffs – Appreciating the importance of bluffs

-

The shoreline of Puget Sound is rimmed by slopes and steep bluffs that range from five to several hundred feet high. Looking at the bluff faces, you can often see many layers of sand, silt, gravel and clay, which were deposited during the glacial and interglacial periods. As these bluffs erode, they provide the building materials that make up our beaches. Whether the cause is from slide activity or wave action, the sediment falls off the bluffs, where it is carried along the shoreline by wave and wind action. These are often referred to as feeder bluffs, and can feed miles of beaches, creating shore forms such as spits and barrier beaches.

Specific compositions of sand and gravel along a beach are important to many species of marine life. Surf smelt, a forage fish, lay their eggs in the high intertidal zone, in fine gravel and sand substrate. Sand lance, or candlefish, another important forage fish, spawn in shallow water at high tide on sand-gravel beaches, or sometimes on sand beaches. Forage fish are important food sources for salmon, seabirds and other marine species.

Sand and mud beaches support eelgrass beds, which are important habitats for small fish and other marine organisms. Pacific herring, an important forage fish, deposit their eggs on eelgrass blades. Larger fish like salmon depend on healthy eelgrass beds for their survival, as do Dungeness crabs, seabirds, and several other marine species.

-

Replacing Bulkheads with Natural Solutions

-

Natural beach

Soft shore protection

Bulkhead Alternatives to shoreline armoring, known as soft-shore protection, have been developed to help protect the shoreline. Soft-shore protection projects rebuild the upper beach area to provide protection of property and homes while preserving natural beach functions. These approaches use natural materials such as gravel, sand, logs and root masses to absorb wave energy and reduce erosion. One approach is to bury large rocks or concrete blocks below the beach surface, which are used to anchor large woody debris or drift logs. Placement of soft-shore features are carefully engineered, and should not be attempted without assistance by an expert and obtaining the necessary permits.

Sometimes soft-shore protection comes to you! The natural presence of driftwood and other large woody debris helps to retain sediments and absorb wave energy. If you find them washed up on your beach, leave them in place. Also, intertidal plants, dune grass and other berm vegetation can greatly increase the resilience of beaches to storm waves. Native vegetation on shorelines and bluffs are your best first line of defense against erosion.

-

Recognizing How Bulkheads Change the Shoreline

-

Bulkheads, seawalls, and riprap are some of the words that describe man-made structures meant to hold back the erosion caused by waves, wind, and tides. This armoring also includes boat ramps, piers, docks, and any other structure on the beach. Such structures contribute to the armoring or hardening of the shorelines of Puget Sound. It is estimated that more than a quarter of Puget Sound shorelines are currently armored.

Bulkheads, seawalls, and riprap are some of the words that describe man-made structures meant to hold back the erosion caused by waves, wind, and tides. This armoring also includes boat ramps, piers, docks, and any other structure on the beach. Such structures contribute to the armoring or hardening of the shorelines of Puget Sound. It is estimated that more than a quarter of Puget Sound shorelines are currently armored.While armoring may serve to protect the bluff against wave erosion, the energy of the waves may be diverted elsewhere, often toward the bottom of the bulkhead. This water movement scoops away sand and may eventually cause the bulkhead to be undermined and lean towards the water. In all cases, however, the wave energy is also directed back towards the beach, scouring away the sand and small gravel, leaving larger gravel and sometimes bedrock in place of the once sandy beach. When several homes or a community have hundreds of feet of bulkhead along the beach, this effect may be more dramatic. The finer sand and gravel may end up being moved from in front of the bulkheads to sites at one or the other end of the bulkheads, due to littoral drift. If the beach was a location where fish like surf smelt or sand lance deposited their eggs, the change of sand and gravel compositions could cause the beach to no longer be a reliable spawning location for these important forage fish. Salmon, seabirds, and many other marine species depend on such forage fish in their diet. Likewise, the change in a beach’s characteristics could mean the end of its ability to support the important habitat provided by eelgrass beds, which are nature’s nurseries for a wide range of marine species. Over the past century there have been significant reductions in the size and number of eelgrass beds in Puget Sound.

Without armoring, long term erosion is generally quite slow, often less than one foot per decade. Some locations of Puget Sound that experience more dynamic wave action have higher erosion rates. Erosion usually does not occur at a constant rate so it is hard to predict erosion patterns. You could experience little erosion of your property for 40 years, and then a landslide removes a large piece of your bluff at one time. Sometimes these landslides are not caused by erosion from wave action, but due to heavy rains, which cause heavy super-saturated soils.

-

Using Plants & Trees for Stability

-

There are times when property owners feel that a tree or several trees should be removed. Unless the tree is a hazard to your life or property, or presents some other major problem, it should be retained whenever possible to keep the soil stabilized. Factors you should consider prior to removal include the stability of the slope, species, age, health, current health of the tree, position of the slope, surrounding vegetation and density of the stand, rooting habit, soil type, and the ability of the tree to sprout after it is cut.

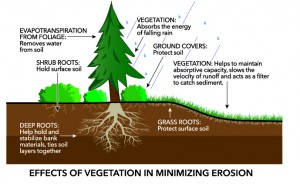

There are times when property owners feel that a tree or several trees should be removed. Unless the tree is a hazard to your life or property, or presents some other major problem, it should be retained whenever possible to keep the soil stabilized. Factors you should consider prior to removal include the stability of the slope, species, age, health, current health of the tree, position of the slope, surrounding vegetation and density of the stand, rooting habit, soil type, and the ability of the tree to sprout after it is cut.EFFECTS OF VEGETATION IN MINIMIZING EROSION:

- Roots hold surface soil and stabilize bank materials

- Helps the ground to absorb water

- Slows the velocity of runoff and traps sediment

- Absorbs the energy of falling rain

- Removes water from soil and transpires it into the air

For those who live along the water’s edge, trees provide multiple benefits by:

- Reducing stormwater runoff. Trees reduce stormwater runoff by intercepting falling rain in their leafy canopies, slowing the force of rain that falls to the ground. The water is held in the bark and leaves, and absorbed through the roots.

- Reducing risk of erosion. Tree root systems help reduce erosion by holding soil in place. Even after being cut, the roots attached to the stump help stabilize soil for years.

- Reducing risk of landslides. The roots absorb the water in the soil and release it back into the atmosphere through a process called evapotranspiration, removing a significant amount of potentially landslide-causing water in the bluff’s soil.

- Protecting embankments. Fallen trees on the beach protect embankments from wave action. These fallen trees may also serve as “sediment traps”, helping build beaches or provide more buffer at the water’s edge. If branches on fallen trees are in your way, prune them instead of removing the trees.

Trees & shrubs for shoreline & streamside erosion control

Marine Shore Trees Marine Shore Shrubs Stream Trees Stream Shrubs Douglas fir Ocean spray Douglas fir Ocean sprey Bigleaf maple Salal Bigleaf maple Red-osier dogwood Madrone Snowberry Western red cedar Red elderberry Western red cedar Vine maple Black cottonwood Sitka alder Willow Serviceberry Willow Shore pine Oregon grape Paper birch Vine maple Evergreen huckleberry Bitter cherry Sitka spruce Vine maple Grand fir Cascara UNDERSTANDING HOW SHORELINES MOVE: Incoming waves often come ashore in a diagonal direction, with the backwash of the waves flowing perpendicular to the beach. This flow carries sediment in a zigzag pattern along the beach, which is known as littoral drift or shore drift. This movement of sediment is called a drift cell. Areas where sediment is deposited is called a “sink” and can be seen in the form of a beach, spit, hook, bar, or tideflat.

-

Limiting the Risk of Erosion

-

To minimize the risks from erosion to your property:

- Establish or maintain a buffer zone between your yard and the water. Buffer zones are areas of densely planted or naturally occurring vegetation composed of trees, shrubs and plants along bluffs and streams. They hold soils in place. This helps to prevent erosion, as well as prevents sediment from washing into the water. When developing your site, do so with minimal disturbance, leaving as much native vegetation as possible, including an undisturbed vegetation buffer along the top of the bluff. If you choose to plant trees on a slope or along streams, use bare rootstock and plant directly into the native soils of your site. Mulching heavily around the planting helps retain moisture and prevents erosion.

- Plant bare areas. Bare soils will erode or invite weeds. When planting, use hardy, deep-rooted native species appropriate to the site, except when it’s over your drainfield. Choose trees and shrubs to stabilize the soil and provide erosion control (Table 1). These species have large, complex root systems that help hold soils.

- Consider building location. Locate your home, outbuilding or patio deck, sufficiently far from the water or bluff so it is not susceptible to erosion or landslides. Resist the urge to trade off safety for the sake of a slightly improved view.

- Divert runoff away from the bluff face. Excessive groundwater and surface water runoff are leading causes of landslides and bluff erosion. Coordinate with neighbors to avoid concentrating runoff, if possible.

- Plan your beach access for minimal erosion. Paths can cause erosion that goes straight to the beach and into the water. When possible, consider sharing access with neighbors to minimize disturbance and cost. Consider building a “hybrid” system (a combination of trail, ladder, winding paths and stairs) to limit disturbance on the bluff.

- Consider natural erosion protection methods. Try using beach logs or downed trees to protect your shoreline. Engineered bulkheads only encourage erosion, often on your neighbor’s property.

- Do not dump yard waste over the edge of your bluff. It sets the stage for future erosion because these piles of green waste smother native plants holding fragile slopes in place. Even small heaps of grass clippings can take years to break down. To learn more, please refer to Guideline 1.

-

Understanding the Causes of Erosion

-

Erosion is the process in which soil and rock from one location are transported to another location where they are deposited. The main producers of erosion are water, wind, and human activities. Puget Sound itself was developed by the erosion caused by water and ice movement from retreating glaciers nearly 15,000 years ago. Even today, erosion is a continual natural process along the shoreline through water runoff, wind, and waves.